An incredible new photo taken by NASA and ESA’s Hubble Space Telescope could have captured the moment new stars were being created.

The dwarf galaxy, IC 3476, lies in the constellation Coma Berenices and is quite a trek from Earth – around 54 million light-years away.

But when the telescope was looking in its direction, it captured a “serene” image that could be telling a much bigger story, NASA says.

While the photo doesn’t look that dramatic, the physical events taking place are “highly energetic”. Scientists explain IC 3476 is undergoing a process titled ram pressure stripping, which drives unusually high levels of star formation in regions of the galaxy.

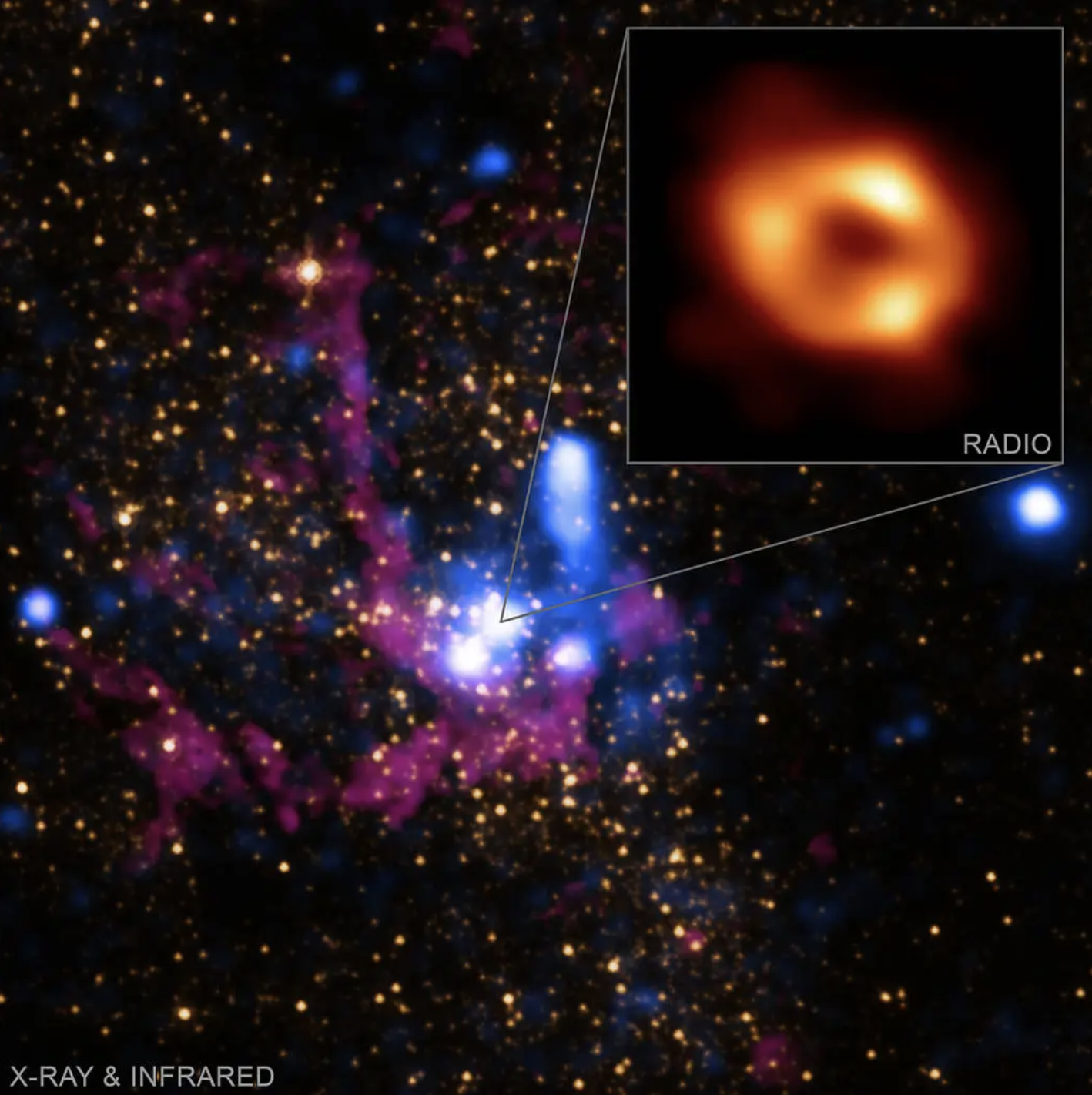

READ NEXT: Giant cavity left behind after one of most powerful eruptions ever from black hole

Gas and dust in space exert pressure on a galaxy as it moves, the resistance is called ram pressure. It can strip a galaxy of its gas and dust that form stars, and even stop it from creating new ones completely. However, it can also do the complete opposite.

When it compresses gas in other parts of the galaxy, it can boost the ability to form new stars, and this is what’s happening in IC 3476, scientists believe. As there are no star formations along IC 3476’s edges, where the most intense ram pressure stripping is taking place, stars are forming deep within the galaxy, and at an above-average rate.

It comes after astronomers revealed they are a step closer to understanding what’s causing mysterious bursts of radio waves from deep space. Two NASA X-ray telescopes observed fast radio bursts within minutes of each other – and they can be as powerful as the energy released from the sun within an entire year. The light, like a laser beam, makes it easier to set them apart from cosmic explosions in the void.

READ NEXT: Secrets of 240-million-year-old ‘Chinese Dragon’ revealed by palaeontologists

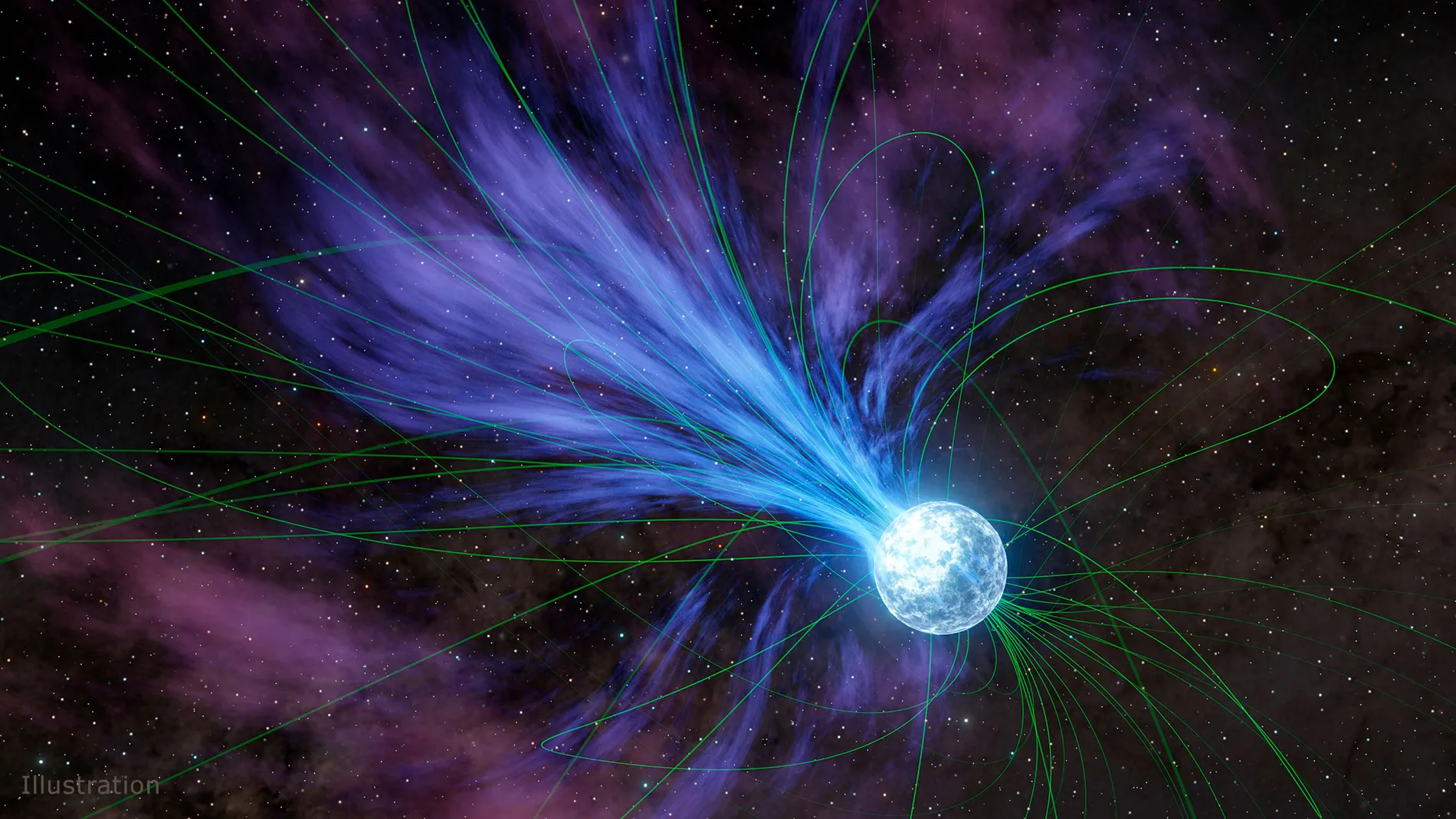

Before 2020, any waves that were traced were found to have come from outside our own galaxy, so they were too far away to study. But then a fast radio burst erupted in our galaxy, from the collapsed remains of an exploded star (magnetar).

Then in October 2022, the same magnetar produced another burst, when it suddenly started to spin faster, moving at around 11,000 kph. The burst was recorded between two ‘glitches’ – when it spins – but trying to slow it down would need a heck of a lot of energy. However researchers found in between glitches, the collapsed star did slow down.

“Typically, when glitches happen, it takes the magnetar weeks or months to get back to its normal speed,” said Chin-Ping Hu, an astrophysicist at National Changhua University of Education in Taiwan and the lead author of the new study.

“So clearly things are happening with these objects on much shorter time scales than we previously thought, and that might be related to how fast radio bursts are generated.”

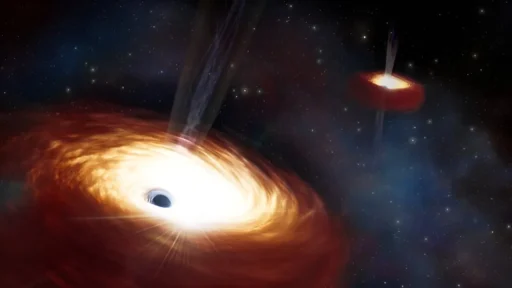

It also comes after the space agency released remarkable photos of two galaxies colliding with each other, something that reads out of a sci-fi book.

READ NEXT: Sun erupts most powerful solar flare in 7 years as experts issue warning over GPS and satellites